‘12

Cerisaie

Sweetheart Cherry leafing out

Our orchard planting continues. We've planted fourteen more apple trees, this round on M7 semi-dwarfing rootstock. Varietally, there's quite a bit of overlap with our last round of planting: two more each of Northern Spies and Early Goldens; one more each Wagener, Liberty, 20 Ounce Pippin, and Yellow Transparent.

We've planted three Honeycrisps (in addition to a fourth tree we planted about a month earlier in the middle of the old orchard). We planted a Grimes Golden, its ancestry tracing back to the Vashon orchard. Somewhat more obscure is the Jon Grimes (more commonly known as Jonagrimes), originating from the same orchard.

As our fervor for apples increases, we've found ourselves making a list of cultivars that we'd like to plant in future years. One such prospect, the Cox's Orange Pippin, couldn't wait. We had to acquire and plant it immediately. This apple is one of the most widely celebrated apples of England, but is rarely grown in the United States due to its very specific climate needs. It has a reputation of being difficult to grow, but since our climate is very similar to England's, we're feeling optimistic.

Cerisaie is the French word for a cherry orchard. There are already quite a few cherries growing on the property, which may be the descendants or rootstock of the Royal Ann cherries my family once grew here. We've begun adding to these, and have planted Lapin, Sweetheart, and WhiteGold varieties. We've grafted others to rootstock, and will soon have them in the ground.

You might think this sounds like enough to be planting for one year. Fear not, friend — we're unfamiliar with moderation. We've also planted a pair of almond trees, an apricot, four frost peaches, and a variety of pears to complement the pears and quinces already growing in the orchard. My tastebuds are reeling as I contemplate how much fruit I'll be eating.

‘12

Words for rain

Gossiping about neighbors

Hushing twilight frogsong

Chattering on the rooftop

‘12

Tending the Ancients

Epiphytic Licorice Ferns and Carpet Moss on the Gravenstein tree

The orchard on Bainbridge Island was planted by my great-grandfather in 1920. The trees are wizened elders: scabbed, pocked, and verdant with moss. On Vashon Island is a sister orchard, also kept by our family. The Vashon apple trees are even more methuselan, having been planted at the turn of the twentieth century. Both orchards persist in bearing apples — perhaps not as many as they once did, but even now we encounter bumper crops that bend the branches near to earth.

The trees in both orchards have been gently neglected. Watersprouts reach for the sky, and jumbled lower limbs lay lattice-like across one another, screening the sunlight. Between healthy boughs are dead limbs and jutting stumps of broken branches.

Our arboreal adulation reinvented us as apprentice caregivers. We've begun pruning, equipped with only an orchard ladder, rudimentary knowledge, and several sharp cutting implements. This year we've focused on removing dead wood, cutting old stumps flush to the trunk (so that they have a chance to heal), and trimming out broken or especially tangled branches to bring light to those below.

Pruning the colonnades of watersprouts and removing dead or errant branches is a process that will take years — disregarding all the maintenance required by trees' troublesome tendency to continue growing. The task also grows unexpectedly as we discover hidden trees: apples cloistered in a bamboo thicket, pears amidst the locust.

‘12

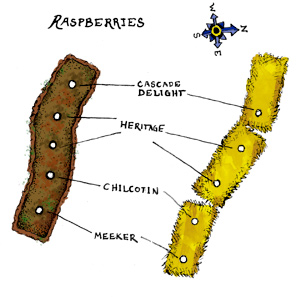

Raspberries

Raspberry leafing out

Planting schematic

One of the joys of breathing life back into the farm is the necessity of experimentation. Among our recent science experiments is the fledgling raspberry patch:

Some areas of the land have rich, loamy topsoil, enriched with iron or infused with nitrogen from years of cattle fertilization. Other patches are resource-scarce, with clay or jumbled rocks closely abutting the thin layer of soil on the surface. All told, we don't have a surplus of excellent soil, which forces us to be creative.

Our raspberry experiment uses straw bales as planting beds. For each of our five pairs of raspberry plants, we planted one plant in the bales and one in a traditional turned-earth garden bed. We have four varieties of raspberries (see the schematic I drew at right). We're hoping both sets of plants will thrive.

If the bales turn out to be a viable planting method, we may find ourselves using them to make some of the less fertile parts of the land productive parts of the farm.